Céline Lavail first crossed Michael Jackson’s path in 1996 while the superstar was staying in Monte Carlo, but it was only two years later that Michael, particularly touched by one of her creations, commissioned a first piece for his private collection. This was the beginning of a collaboration that gave birth to several commissioned portraits of the star : "Peter Pan", "Inspiration", "Archangel", "Allegory" and "Scared of the Moon".

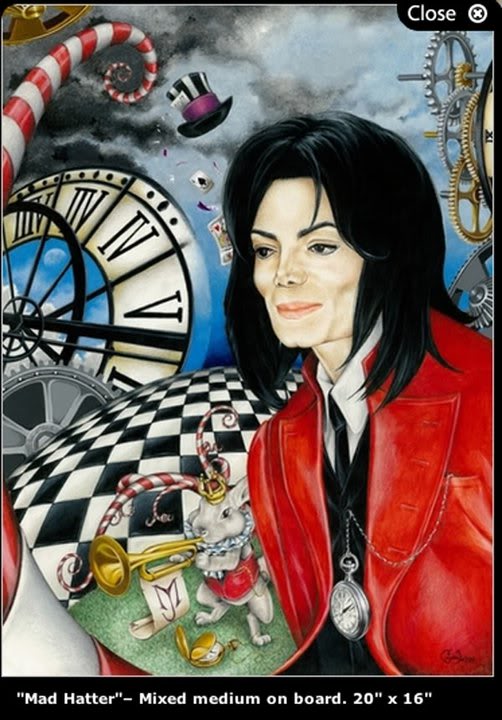

"Mad Hatter", the very last piece produced for Michael Jackson that was meant to be delivered to him during the Summer of 2009 will be auctioned in early 2010 within the frame of "The Official Michael Jackson Opus" charity auctions.

Most of the pieces that Céline Lavail created for Michael Jackson are featured in the luxurious publication "The Official Michael Jackson Opus" (Kraken Opus Ed.). The Opus features tributes to the star by those who new him best, worked with him and those inspired by his work.

Celine tells her story:

"I was only 17 years old when I first met Michael Jackson. It was 1996 and he was staying in Monte Carlo for a few days. I’d always been a fan of his music and I’d heard he was also a massive art lover. At that time I used to draw and sketch a lot as a hobby. My plan was to go to his hotel and give some of my pictures to his security staff in the hope that they would reach him in some way. When I got there with the pictures, the security guards handed them to a member of his staff.

Amazingly, I was told that Michael wanted to see me. I couldn’t believe it. I was shaking. Thank god I had the drawings — if the worst came to the worst, I could always hide behind them. Suddenly I was being ushered up to his suite, by now terrified. As I entered the room — surrounded by his aides, people in suits — Michael was just standing there, welcoming me with a big smile. That relaxed me a little, but I knew things would be difficult because my English was not so good. I lived in Perpignan in France at the time, a town near the Spanish border, but I had only learned some of the language at school. “I’ve done something for you,” I said. He stared at my pictures. I’d brought five or six sketches, they were rough but I was pleased with them. “You study art?” he said. I told him that I didn’t and this caused the most unusual reaction: he started clapping. “You’ve got a gift,” he said. “It comes from God, you have to cherish this gift and feed it. Please keep on creating, I want to see more.” I felt proud and embarrassed at the same time. It was such a surreal experience. As I walked out of the suite, one member of his staff handed me a piece of paper. On it was the name of Michael’s assistant with a telephone number. I was told that “Mr Jackson would love to see more art,” and I walked away from the hotel, my head spinning, lost for words.

Almost immediately, I started sending sketches to Los Angeles without knowing exactly if they would eventually end up in Michael’s hands. I soon found out that they were getting through: I would sometimes get feedback from him or suggestions. I would ask Michael for hints. I wanted to know what I should work on and his answers varied from a single word like “royalty”, or a very precise scene he wanted to see. Most of all, he said, he wanted me to pull from my guts and be creative. He even called one day. The phone rang and a voice enquired, “Celine?” I recognised him straightaway, but I couldn’t believe it. Michael Jackson, the man who made Thriller, the dancer who moonwalked at the Motown 25 show, had called me. Still it was hard to match that person to the voice because he was so humble and normal. I had sent him some sketches of Peter Pan and he told me he loved them. I’d been drawing other Disney characters for him, but he told me to be “more creative.”

“You’ve got imagination, I know it,” he said. “Do something that has never been done before.”

He told me several times to study and to be inspired by the great artists. I was astonished when I realised how knowledgeable he was when it came to classic art. He told me about Michelangelo, Delacroix, Leonardo Da Vinci and Nicolas Poussin. We talked about modern popular illustrators such as Norman Rockwell or Scott Gustafson. In his hotel room there were often piles of art books. He was very fond of the figurative style and enjoyed everything related to fantasy. Following his advice I paced up and down most of Paris’ museums, staring at the work of all the greatest masters and worked hard to improve my craft.

By 1999, I decided it was time to show Michael the new piece I’d been working on: a portrait of him as Peter Pan. I knew he would love it, he was so fond of the Disney character. He was staying at the Ritz in Paris so I arranged a visit. When he saw the picture, he opened his eyes wide and hugged me really hard. “I love Peter Pan,” he laughed. “I am Peter Pan!”. That wasn’t all. Michael was about to commission an artwork from me. He pointed to the delicate mouldings on the walls that represented cherubs and softly explained the exact scene he had in mind: “Babies are adoring me with love and affection, which represent peace, love and harmony of all races,” he said. This artwork would later be named Inspiration.

During the creative process of this piece I occasionally received instructions from Michael’s part, asking me to add or remove details in the composition. In the picture, Michael is pictured reaching for the finger of a cherub who is Prince, his first son. When he finally found out about this “detail” he seemed happy. He believed I’d been inspired by Michelangelo’s Creation Of Adam. At first, this painting was hung in Neverland. Later it would be reproduced on the carts that were used to drive around the ranch, though I don’t know where they are now. Overall, I think he had five paintings of mine, plus a jacket I made for him and a book.

Looking back, one moment summed up our collaboration. I remember that Michael loved the fact that Michelangelo — one of his favourite artists — had inspired generations of others. His great achievements were still widely acknowledged centuries after his death. One day, I had a very interesting discussion with him about the power of art and the way it can transcend life, space and races. At the end of our meeting, Michael handed me a piece of paper. On it was written, “I know the creator will go, but his work survives, that is why to escape death I attempt to bind my soul to my work.” He looked at me. “Michelangelo said this,” he explained, though in hindsight, it’s probably a perfect way with which to describe Michael Jackson’s life".